When October comes, I always think about the new olive oil, from the olives harvested between now and December, at least where I come from in Abruzzo, Italy. I still remember those long nights in the frantoio (the mill where you take your olives to be pressed). As a teenager I’d watch, fascinated, and later in life I returned as an auditor, taking samples of freshly pressed oil to the lab… and, of course, tasting it on warm homemade bread. Unbelievable. It’s been a while since I’ve done that, but every October those memories return, along with the question: where will I find good, fresh oil this year?

Meanwhile, here in London, friends often ask me: “What’s a good oil I can buy?” But the real question is: “What’s a decent oil I can find in an ordinary supermarket?” And that, believe me, is not easy. There are thousands of bottles on the shelves: flashy labels, words like cold, fresh, healthy, organic plastered everywhere. It’s overwhelming.

So let’s reframe the question: How can I choose a decent oil without being tricked?

Think of it like shopping on a website with thousands of products. You don’t scroll through them all; you apply filters until you’re left with the real options worth considering. That’s what we’ll do: apply filters, one after another, cutting away the rubbish. By the end, you’ll probably have eliminated 90% of what’s on sale, and that’s good. With olive oil you need to be a food snob in the good sense: read labels, ask questions, and never settle for bargain rubbish or flashy tricks.

Filter 1: Type of Oil

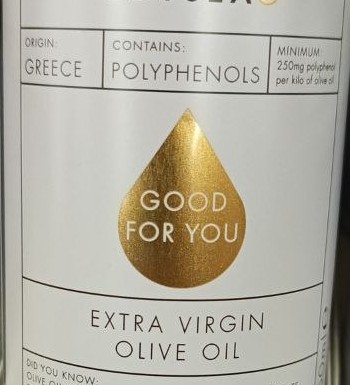

To start with, the minimum requirement is extra virgin olive oil (EVOO). Everything else, whether “Virgin Olive Oil”, “Olive Oil” or “Olive Pomace Oil”, sits on the same low level: defective, lower quality, often refined, and far from what real olive oil should be. In the case of Pomace Oil, I’ve written more here: Pomace Olive Oil – Why It Shouldn’t Be on Restaurant Tables.

In my view, none of these oils deserve a place on the shelves. Forget them..

Filter 2: Container

The bottle or container matters.

Plastic: out. Not only because of possible migration into the oil (when they say a plastic is “food safe”, what they really mean is “we haven’t proven it’s dangerous yet”). But also because plastic is cheap. No proud producer would ever put quality oil in plastic.

Clear glass: out. Olive oil is sensitive to light. If it’s in clear glass, it’s more about marketing (so you admire the colour) than protecting the oil.

Ceramic bottles: attractive, but mostly overpriced gimmicks. Too often used to sell mediocre oil at premium prices. Same goes for fancy perfume-shaped bottles. Marketing tricks.

Dark glass or tin: in. These protect the oil properly and are the choice of serious producers.

So after this filter, you’re left with dark glass bottles or tins.

Filter 3: Price

Quality EVOO cannot be cheap, but expensive oil is not automatically good either.

Here’s the reality:

Buying directly from farmers in Italy today, I’d expect to pay €12–15 per litre (harvest 2024), straight from their main stainless steel container.

In the UK, you will not find EVOO for less than £10 per litre.

That means around £8–10 for 750ml or £50 minimum for 5 litres. This is for basic EVOO, often with no great flavour.

Truly great oil, the kind I’d happily buy from small producers, costs at least £20 for 750ml, £25–30 per litre, or about £120 for a 5-litre container.

So the filter is simple: if it’s too cheap, it isn’t good.

Filter 4: The Label

Labels are the trickiest part: they’re full of claims, most of them meaningless. Still, here are the things that matter:

The label must say Extra Virgin Olive Oil, with the wording: “superior category olive oil obtained directly from olives and solely by mechanical means.”. Nothing else is acceptable.

Cold pressed: choose only oils that show this on the label. Legally, it can appear only if the oil was extracted below 27°C. This matters because low temperature preserves antioxidants, flavour, and all the nutritional value of the olives.

Origin: choose oils that clearly state a single country — Italian, Greek, Spanish, Portuguese, Cypriot. If it just says European Union, walk away. That means it’s a blend of whatever was cheapest at the time.

PDO/PGI: these labels (Protected Designation of Origin / Protected Geographical Indication) add assurance of authenticity and traceability. They don’t guarantee greatness, but they do guarantee minimum standards.

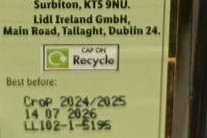

Harvest date: best if it states month and year. Year alone is acceptable. No harvest date usually means lower quality or hiding something. Some bottles show “Crop XXXX–YYYY”, which means the harvest stretched from late XXXX into early YYYY. That’s normal, but without a month you can’t know how fresh it really is.

Best Before Date: a rule, don’t choose anything with less than 12 months left. That’s the minimum.

Producer and bottler: ideally the same. Otherwise, the bottler should clearly name the mill or cooperative. The law requires a company name and address on the label, but if all you see is something vague like “Packed in the EU”, with no real traceability, treat it as a warning sign..

Polyphenols (Phenols): if the label shows the polyphenol content, it’s not just marketing — by law it means the oil has been tested and certified. High polyphenols indicate the oil is, or at least was at bottling, of superior quality: richer in antioxidants, fuller in flavour, and better for health.

Other legal details (nutritional values, batch numbers, address) must be there, but they tell you nothing about quality.

The Final Test: Taste

Once you’ve narrowed it down with all these filters, the ultimate test is always taste. Fresh EVOO should taste fruity, bitter, and peppery — that’s the polyphenols. Flat, greasy, or rancid flavours? That’s poor or old oil.

I’ve done my share of tastings and lab tests, and in future I’ll share more of those results. For now, you’ve got the tools to filter out the rubbish and find something decent on the shelves. Select wisely, enjoy the oil, and if you find an excellent EVOO here in the UK, let me know. I’d be glad to hear about it.