8–10 minute read

Gluten, Processing and How to Choose Better Baked Foods Today

For about two thousand years, millions of people have repeated the prayer:

“Give us this day our daily bread.”

Bread was never just food. It was life. It was work. It was something that belonged to everyday life.

Among my best childhood memories is of my grandmother making bread at home. She did it for as long as her strength allowed. The sourdough starter lived in an old drawer, just like a simple household tool. Hard like a stone. Then she would take a piece of it, put it in water, and quietly begin the preparation for the next day.

She also had one of those old sayings:

“On Friday and on Tuesday, you do not marry, you do not leave, and you do not start a craft.”

And yet, for a reason known only to her, bread was always made on Fridays.

Friday was the day of slow preparation. And in the afternoon, there they were: eight or ten loaves of beautiful bread, and that smell that fills a house and stays with you for life.

That bread was made of flour, water, time and hands. Nothing else.

Today, bread still looks like bread.

It still smells like bread.

But it is no longer made in the same way. And that is why the question matters today more than ever: What happened to our bread?

Bread and baked foods have always been everyday staples. Yet very few people truly understand how much bread has changed. And honestly, today it would be wise to avoid many modern breads and baked products and certainly not eat them “daily”.

So, what has changed?

Pretty much everything.

The grains have changed, selected and hybridised.

The flour has changed, regularly processed to remove most of its beneficial nutrients.

The fermentation has changed, replaced by fast industrial raising to make bread in the shortest possible time.

The ingredients have changed, with the addition of substances that were completely unknown until recently, such as emulsifiers, sugars, anti moulding agents and other industrial aids.

The result is bread and baked products that are highly processed, harder to digest, and full of substances that only serve the needs of industry. At the same time, people are now exposed to higher and more frequent amounts of gluten. This helps to explain, at least in part, the increase in people reporting intolerance to gluten, to wheat in general, allergies and digestive problems.

With this post I want to share a few practical suggestions to help you choose better baked products, mainly by learning how to read labels and knowing what to avoid.

Before we get to the label, however, we must understand what has happened to flour itself.

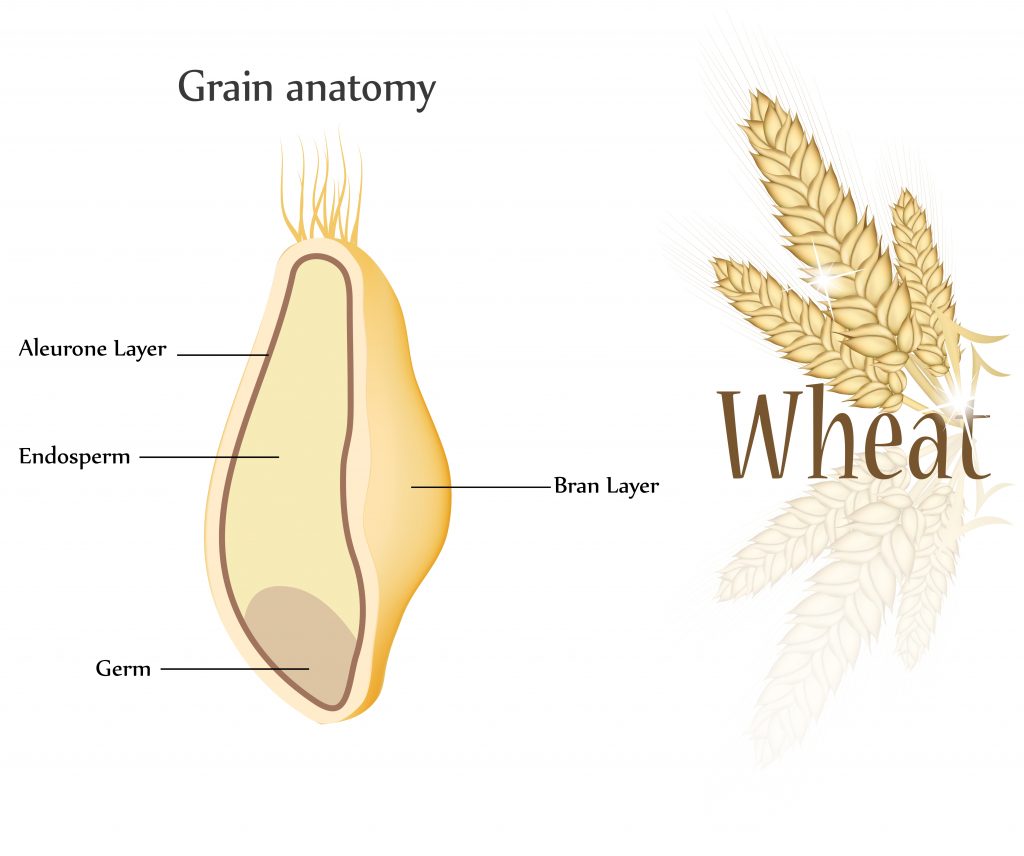

The structure of a whole grain

The phrase “whole grain” sounds almost like something special. A bit like “extra virgin olive oil”. It sounds premium. But in reality, extra virgin olive oil should simply mean oil obtained by cold extraction from olives, nothing more. In the same way, wholegrain flour should simply be the grain in its natural state, milled as it is, without stripping anything away.

Each wheat grain is made of three main parts.

The bran is the outer layer of the grain. It is made mainly of fibre, but it also contains essential healthy fats, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. It protects the inner part of the grain.

Inside we find the germ. This is the embryonic part of the grain, the part of the seed that would grow into a new plant. It is very small, but nutritionally the richest part of all. It contains healthy fats, protein, vitamins and active enzymes.

Finally, we have the endosperm, which means “inside the seed”. This is the biggest part of the grain and is made mostly of starch with some protein. It is meant to nourish the germ as the seed grows. This endosperm is basically what becomes white flour once the bran and germ are removed.

Impact of the milling process

When the bran and germ are removed, enzymes, natural oils, antioxidants, vitamins and minerals are removed with them.

Why is this done?

Because enzymes can become unstable and change behaviour.

Because natural oils can oxidise and go rancid.

Because bran changes the colour and handling of the flour.

Because white flour behaves better in modern industrial bakery machinery.

Because for decades consumers have been trained to think that soft, white bread is the superior product.

There is also a strong economic factor. Bran and germ, once removed, are sold separately for “healthy” niche products and often at higher prices than the original flour. So the flour is stripped to suit industrial production, and what is removed is sold elsewhere for profit.

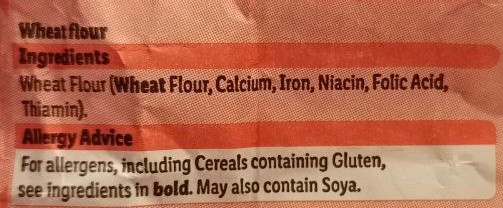

White flour becomes so nutritionally poor that governments had to intervene. In the UK, white flour must legally be fortified with calcium, iron, niacin and thiamin to prevent serious deficiencies.

Is this fortification done because of love or care for the consumer? Nope. It is done because the law requires it.

And even then, what is reintroduced is still far less than what is removed. Fibre, vitamin E, natural oils and many protective compounds are simply gone.

About gluten

Once flour is stripped of bran and germ, what remains is mainly starch and gluten.

Modern wheat varieties have been selected to give strong gluten structure because this is useful for fast, high speed industrial baking. This already increases gluten exposure.

On top of this, extra gluten is often added deliberately as “vital wheat gluten” to improve volume and structure. And gluten is also added to many other foods as a binder and protein booster. So exposure keeps rising from multiple directions.

Then comes the second major issue. Fermentation.

Traditional bread was fermented slowly, sometimes for many hours. During this time part of the gluten was naturally broken down.

Modern bread is mixed fast, loaded with yeast and fermented in a very short time. This means that more gluten remains intact in the final bread.

The result is simple.

More gluten in the grain.

More gluten added to food.

More gluten left intact because fermentation is rushed.

No wonder many people today suffer from bloating, fatigue, brain fog and digestive discomfort after eating bread. Some are coeliac, many are not. But one thing is certain. The population today carries a much higher gluten load than in the past.

Other extra ingredients in bread and baked products

The problem with modern bread is not only flour and gluten.

To improve texture, softness, volume and shelf life, the industry adds other substances.

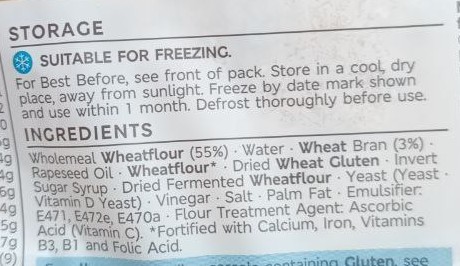

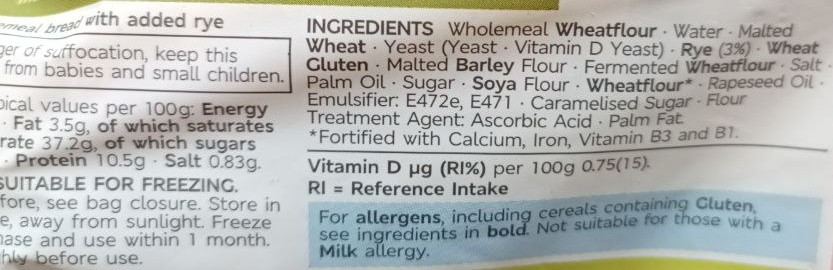

Emulsifiers

These make bread airy and soft. On labels they appear as E471, E472, E481, E482, E322 and similar codes.

There are scientific studies linking some of these commonly used emulsifiers to:

- Disruption of the gut microbiota

- Damage to the intestinal protective mucus layer

- Increased intestinal inflammation

- Worsening of irritable bowel conditions

- And even higher risk of bowel cancer and metabolic disease

What keeps bread soft for weeks on a shelf is not the same thing that keeps the intestine healthy.

Seed oils

Many industrial breads contain seed oils to improve texture, shelf life and machinability.

They are there for industrial convenience, not for your health.

These oils, when consumed in excess as happens in modern diets rich in ultra processed foods, contribute to inflammation and metabolic stress in the body. Again, they are added to serve the needs of production, not the well being of the consumer.

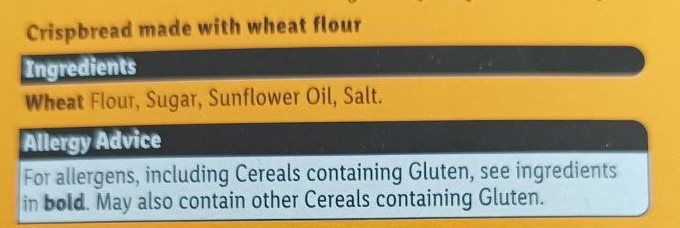

Sugars in bread

Sugar is added to bread to improve flavour and crust colour and to feed fast yeast.

If you see sugar on a bread label, just leave it. And the same applies to all its “nicer sounding” versions such as malt extract, barley malt extract, malt syrup, inverted malt and similar terms. They all mean one thing. Added sugar.

Metabolic effects

Once you remove bran and germ, starch becomes much faster to absorb into the bloodstream.

Add to this fast fermentation, sugars, emulsifiers and industrial fats and you end up with bread that behaves almost like a sweet.

Blood sugar rises quickly. Insulin follows. Energy spikes and crashes. Repeated day after day, this pattern contributes to weight gain and insulin resistance. This is no longer bread. This is a industrial carbohydrate delivery system.

Wholemeal and wholegrain. What is the real difference

Both wholemeal and wholegrain legally mean that bran, germ and endosperm are present in the flour. But they may not arrive there in the same way.

True wholegrain flour is milled from the intact grain in one pass, keeping the natural structure of the grain together.

Many wholemeal flours are produced by separating the grain into white flour, bran and germ and then recombining them later. In some cases the germ is heat treated to prevent rancidity.

Both count as wholegrain on paper. But structurally and biologically, intact wholegrain flour is the better product.

The real deception, however, is elsewhere.

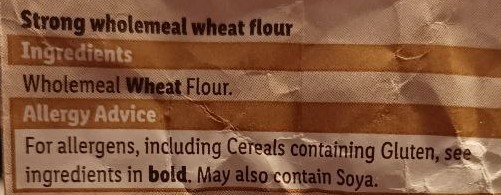

When you read on a bread label “Wheat flour”, what you are really reading is nutrient stripped white flour, even though the word “white” never appears.

When you read “Wheat flour (calcium, iron, niacin and thiamin)”, again you are looking at a flour or a product made from nutrient poor white flour, which has been artificially fortified only because the law requires it.

And when you see:

Brown bread

Multigrain

Granary

With wholegrains

Very often this simply means white flour with some bran, seeds or colouring (sugars) added back for appearance. Not real wholegrain bread.

Conclusion and how to choose better bread

So what is the message?

Bread is not the enemy. Industrial bread is the problem.

Reduce it as much as you can.

Do not be fooled by colour, by marketing words, or by long ingredient lists that sound reassuring. Choose real flour. Choose real fermentation. Choose real bread.

Read labels. A real, honest everyday bread should show only four things:

Wholegrain or wholemeal wheat flour

Water

Salt

Yeast or sourdough starter

If you read sugar in any form, leave it.

If you read malt extract, barley malt extract, malt syrup, inverted malt or malted barley, understand that this is sugar with a better sounding name and a high glycaemic impact.

And if you see “Wheat flour (calcium, iron, niacin and thiamin)”, do not be fooled. It is poor quality flour

If you see wheat flour as the main ingredient, remember. That is refined white flour.

The same applies to all baked products.

And if you pay more for something advertised as sourdough, read the ingredients carefully. If it contains sugar, yeast, emulsifiers or oils, then no, it is not real sourdough. It is an industrial imitation (and yes, they can imitate the crust, the colour and even the acidule flavour).

Prefer artisan bakeries over plastic wrapped supermarket loaves whenever possible.

And why not make bread yourself?

There are methods today with high hydration and no kneading that make bread making simple and enjoyable. Your loaf may not be perfectly shaped. It may not be soft like supermarket bread. It may not look perfect. But it will be real bread. Bread you could honestly wish to eat daily.

If you know someone who loves bread, share this article with them. Here the link: https://scientialex-foodsafety.co.uk/what-happened-to-our-bread

If you have comments or questions, send them to my email.

Thank you for reading.